How the EU broke up with the City but not with its tax havens - Part 1 Barnier was right, yet...

Three years ago, the EU stroke a post-Brexit deal with the UK. The City of London then ceased to be part of the single market, the EU claimed. True, except for its darkest recesses.

January 6, 2021. Michel Barnier is Edwige Chevrillon's guest on BFM Business television. The Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) between the European Union and the United Kingdom has been signed two weeks earlier, on December 24, 2020, ending three and a half years of negotiations. The economic journalist wants to make sure there was no deal when it came to future relations with the City of London.

"There is still the whole service component to be negotiated... The service component, when will it be implemented?", she asks.

"There have been no negotiations on financial services," her guest replies, a little surprised. “Some services are concerned” by the TCA, “but there are no and there will be no negotiations on financial services. All financial services, which I know well because I regulated them for five years as Commissioner, are subject to what are called possible equivalences, which are unilateral decisions that we will or will not give, that we may or may not take back from the United Kingdom, as we did with the United States or Japan. So there will be no negotiation. There will be equivalences that will be given according to a very important criterion... that is the financial stability of the European continent and in particular of the euro zone...".

In other words, the Union was to seize the opportunity of Brexit to protect Europeans from the "animal instincts" that rule the City of London, even if it meant cutting itself off from it.

Michel Barnier is telling the truth: he presented some 40 pieces of legislation on financial services during his time as Internal Market Commissioner (2009-2014), in line with the post-crisis G20 agenda meant to “moralize” the financial sector.

He is also right about the agreement with the UK : four and a half years after the referendum, three and a half years after the start of negotiations, the Union has sealed on December 24, 2020 a deal with little or no provision for financial services, unlike other sectors such as agriculture, energy or transportation. This remains true until today.

It is also fair to say that the Commission has full power to grant, permanently or temporarily, an “equivalence status” to any foreign country, and to withdraw it in the same way.

But on one point, the Brexit negotiator in him seems to have lost the memory of the Commissioner he had been. As he talks on BFM, certainly the UK has not received equivalence (except for markets infrastructures, i.e. central clearing and securities depositories) but its satellites have been copiously served. The secretive British Crown dependencies Jersey, Guernsey and the Isle of Man, as well as Bermuda, an Oversea territory, have been linked to the European Union for several years by these “unilateral decisions” he talks about. They still are.

A foot in the door of the internal market

Global markets pose dilemma to national or supra-national legislators and regulators : how to facilitate international trade without giving up their regulatory autonomy. The short answer is : talk, seal deals and share power.

In financial services, yet, EU's response differs from the usual one. Rather than entering into free trade agreements based on reciprocal concessions in terms of customs duties, standards or quotas, it has developed a particular instrument called “equivalence”.

Granting equivalence to a foreign jurisdiction consists in unilaterally recognizing that the latter has legislation and a control system sufficiently similar to its own so that operators (banks, insurance companies, fund managers, etc.), by submitting to the regime of this third country, are presumed to comply equally and automatically with their own legislation.

So-called “third country regimes”, where possible equivalence decisions are embedded, became even more central after the 2008 crisis and the successive meetings of the G20 to establish a "new regulatory agenda" or, as Michel Barnier put it in simple terms, that, in the future, "the banks pay for the banks". This tightening of the screws risked to disrupt capital flows between the EU and foreign jurisdictions. Hence the interest of “equivalences” or, in other words, gateways designed not to split up globalized financial services markets.

From Chile to Hong Kong, from Malaysia to Serbia, from Dubai to Brazil, from Singapore to Monaco, from Switzerland to South Africa, the third country regimes have aroused enormous interest throughout the world and among financial players. In the post-crisis, re-regulation years, the requests for an equivalence status flooded the Commission.

Let us take the example of rating agencies. Financial ratings (as AAA, AAB etc.) give indications on the level of solvency of public or private issuers or the financial soundness of a given financial vehicle. They are used in particular by the managers of mutual funds who must respect a certain risk and investment profile. If the Luxembourg manager of an "Asia" UCITS fund wants to include Japanese securities in his portfolio, he could, thanks to the equivalence granted to Japan under European regulations on rating agencies, rely on the ratings assigned by Japanese agencies, even if the latter are not supervised by any European authority but by a Japanese one. The Japanese issuer, for its part, will not have to seek the services of analysts based and supervised in Europe to place these securities by European investors. As Japan does the same for European ratings, European issuers do not have to solicit Japanese agencies to place their securities in Asia. In short, the two blocs trust each other because they consider each other to be "equivalent".

The case of the rating agencies is simple. Others, less so.

The EU law on the capitalization rules for banks and investment firms provides for no less than eight different types of equivalence (mostly depending on the type of risk exposure against which capital requirements are computed), and the regulation on the solvency of insurance and reinsurance companies, three. But the principle doesn’t change. It is to allow European companies to rely on the rules and supervision of such or such third country to ensure the compliance of their foreign subsidiaries with European law.

More than 200 decisions in favour of 40 jurisdictions

It is this type of arrangement about which Chevrillon grilled Barnier live on set on January 2021. When he replied that none was granted to the UK, opposite to "the United States and Japan", she did not follow-up. Yet, she could have had.

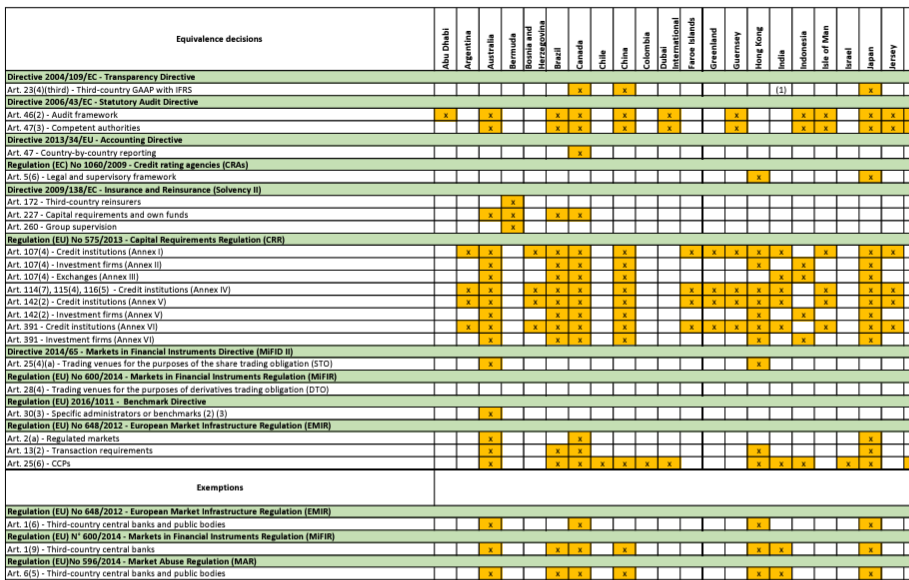

From Chile to Hong Kong, from Malaysia to Serbia, from Dubai to Brazil, from Singapore to Monaco and from Switzerland to South Africa, the third country regimes have aroused enormous interest throughout the world and among financial players. The requests for an equivalence status rained down on the Commission in the “re-regulation” years. Many operators risked having their global operations disrupted by regulatory "barriers", so the applicants. The Commission heard very well and responded generously. By its own count, it had granted more than 200 decisions, permanent or temporary, by February 2021 to some 40 jurisdictions around the world, in all kinds of financial services (audit, insurance, trading venues, prospectus, credit ratings, capital requirements for banks, etc.).

Equivalence decisions, as of November 2023 (extract)

In the years of “re-regulation” following the financial crisis, British Members of the European Parliament, their fellow diplomats and ministers in the Council, as well as active relays of British interests within the Commission were busy changing the small prints of those laws and framing the most “business friendly” implementing measures. Among the nitty gritty of the post-crisis negotiations, third country regimes were of peculiar importance, for a good reason : they were to shape the City of London satellites future relations with the rest of the world.

When, in early 2021, Michel Barnier says “there are no and there will be no negotiations on financial services” between the EU and UK, the dependencies of the British Crown have been plugged in to the internal market for several years and were to remain so all along the negotiations and after UK’s exit from the single market.

On June 13, 2013, Jersey, Guernsey and the Isle of Man, as well as many others more or less exotic jurisdictions, were granted “equivalence” when it came to the quality of auditing services.

The decision is signed by Michel Barnier. In doing so, Barnier prolonged a regime that his predecessor, the Irish Commissioner Charlie McCreevy, a professional accountant, had put in place while harmonizing auditing rules within the single market. At the time Barnier granted equivalence, a renewed audit directive, proposed and negotiated under his auspices, was about to enter into force. Hence, the French man had to supplement the existing decisions by another if those jurisdictions were to remain bound to the single market. The aim remained the same : give “legal security” for the companies listed in the EU (inc. UK and Ireland) but registered (and audited) out of the single market, including tax haven.

This wasn’t just a text book case.

Mines and renewables among Guernsey registered, Frankfurt listed stocks

Auditing, i.e. the preparation and control of financial accounts and balance sheets, is a sensitive issue. A financial scandal goes almost always along fraudulent accounting. No market economy without accurate financial information. Hence the interest in controlling... the controllers, in other words the audit firms.

To declare a jurisdiction equivalent in auditing means letting the authorities of that country ensure that the quality of the process of drawing up the accounts is such as to guarantee their faithfulness and reliability.

As the European Federation of Accountants Accountancy Europe explains : "this equivalence... means that an audit in a third country with an equivalence decision is considered to be a supervised audit with the same level of requirements as in the European Union". Yet, when this third country is a micro jurisdiction of a few tens of thousands of inhabitants, sheltering thousands of funds, (shell) companies and other trusts, and when the risks of capture of the regulators by the industry are multiplied by the concentration of power in the hands of a few, one may wonder whether “equivalence” makes sense at all.

The fact that a company listed on an EU trading venue is domiciled in an "equivalent" foreign jurisdiction does not mean that the company and its owners are seeking to evade EU taxation, legislation or supervision in any way, or that they are trying to launder money.

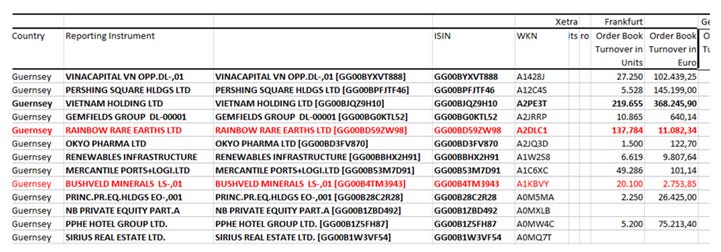

On the Xetra trading platform (Deutsche Börse), on the Frankfurt stock exchange, several mining groups (precious stones or rare earths) are domiciled in Guernsey, like for example Rainbow Rare Earth, controlled by Cypriot tycoon Adonis Pouroulis. Primarily listed in London, their shares remain accessible since the Brexit on the German market place. Another Guernsey registered stake is Renewables Infrastructure Group, a British investment trust, licensed as a closed fund. It holds stakes in more than 80 projects and more than 2000 MW of installed power (the equivalent of 2 nuclear reactors) in 20211.

Issuers listed on XETRA (Frankfurt) and registered in the island of Guernsey

(Screen shot of a sorted listing of Deutsche Börse, Frankfurt. The letters at the beginning of the ISIN code - a code attributed to each and every listed security - indicates the country of incorporation of the issuer. GG refers to Guernsey. NB : companies in the list are also listed on the London SE. December 2020)

These issuers can access investors, cash the reputation gains of being listed on a major European market venue and enjoy the protection against abuse or insider trading offered by the trading framework, without having to pass through the auditing prongs of the German market authority and the German auditors' institute in charge of guaranteeing the quality of the accounts of the companies offering their securities to the public.

A quick search of the ISIN codes on the Euronext Amsterdam exchange shows that a fund created (and largely owned) by Axa Investment Management (AIM), the Paris-based asset management company of the French insurance group Axa, is domiciled in Guernsey since 2006. AIM has recruited top professionals to Volta's board of directors (composition end of 2020): the chair of the audit committee has been a partner of PricewaterhouseCoopers in the islands for 19 years, and the executive director is a senior fund manager, former member of the Guernsey Financial Services Commission, the local financial regulator.

Audited by KPMG Channel Islands, according to the financial documents made available to investors, Volta Finance is a good-sized closed-end fund (with a capitalization of around 226 million in 2021), whose securities custody and administration are handled by the Guernsey branch of BNP Paribas Securities Services. The strategy is decided in Paris, at AIM, and the broker is based in London. Volta Finance has also been listed on the London Stock Exchange for a number of years, although trading volumes are lower than in Amsterdam. While accessing its website, a disclaimer popping up says it “isn’t intented to offer or to promote the offer or sale of the shares… directly or indirectly, in the US or to any US person”. Probably for tax reasons.

The fact that a company listed on an EU trading venue is domiciled in an “equivalent” foreign jurisdiction does not mean that the company and its owners are seeking to evade EU taxation, legislation or supervision in any way, or that they are trying to launder money. Yet, for sure, it has an impact on the obligations of the various European and national regulatory and supervisory authorities meant to protect investors, market integrity, not to say taxpayers in the EU: it frees them from obligations they would have had if the company had its seat within the EU.

In a word, equivalence is risky for the EU as it relieves EU authorities of the responsibility and power to check compliance with its own financial integrity laws on a case by case basis.

And this isn’t just audit.

As for Bermuda, European insurers and re-insurers, who have subsidiaries there, can operate as if they were at home, or almost, while minimizing capital costs and taxation of their revenues.

When, in early 2021, Michel Barnier says “there are no and there will be no negotiations on financial services” between the EU and UK, the dependencies of the British Crown have been plugged in to the internal market for several years, mostly while he was away from Brussels, from the end of his commissioner’s mandate in 2014 until his comeback as a Brexit negotiator in 2016. They have ticked the two boxes in auditing (quality control rules for accounts and supervisory authority for firms) and five of the eight different regimes in banking prudential legislation.

As for Bermuda, European insurers and re-insurers, who have subsidiaries there, can operate as if they were at home, or almost, while minimizing capital costs and taxation of their revenues. The archipelago has been judged equivalent under the long-negotiated reform of the solvency rules in insurance/reinsurance, "Solvency II", since 2016 and never ceased to be deemed so.

Why did the EU Commission cheered those “bridges”, as it calls them? Maybe it was just too difficult to raise them.

Part 3 - Negotiations before the Brexit negotiation

Part 4 - New Brussels Kaiser hires a British duo

Part 6 - Ferber asks McGuiness

Source : wikipedia. Most financial and corporate information about such funds is only available via financial analysts.